import pointblank as pb

small_table = pb.load_dataset(dataset="small_table", tbl_type="polars")

validation_1 = (

pb.Validate(

data=small_table,

tbl_name="small_table",

label="Example Validation"

)

.col_vals_lt(columns="a", value=10)

.col_vals_between(columns="d", left=0, right=5000)

.col_vals_in_set(columns="f", set=["low", "mid", "high"])

.col_vals_regex(columns="b", pattern=r"^[0-9]-[a-z]{3}-[0-9]{3}$")

.interrogate()

)

validation_1Introducing Pointblank

If you have tabular data (and who doesn’t?) this is the package for you! I’ve long been interested in data quality and so I’ve spent a lot of time building tooling that makes it possible to perform data quality checks. And there’s so many reasons to care about data quality. If I were to put down just one good reason for why data quality is worth your time it is because having good data quality strongly determines the quality of decisions.

Having the ability to distinguish bad data from good data is the first step in solving DQ issues, and the sustained practice of doing data validation will guard against intrusions of poor-quality data. Pointblank has been designed to really help here. Though it’s a fairly new package it is currently quite capable. And it’s available in PyPI, so you can install it by using:

pip install pointblankTo run the examples in this post, you’ll need to have a DataFrame library installed. Pointblank works seamlessly with both Polars and Pandas but you’ll need to install at least one of them on your own. We also have a DuckDB example that’s running via Ibis (so, you’ll have to install Ibis with the DuckDB backend for that to work).

How Pointblank Transforms Your Data Validation Workflow

What sets Pointblank apart is its intuitive, expressive approach to data validation. Rather than writing dozens of ad-hoc checks scattered throughout your codebase, Pointblank lets you define a comprehensive validation plan with just a few lines of code. The fluent API makes your validation intentions crystal clear, whether you’re ensuring numeric values fall within expected ranges, text fields match specific patterns, or relationships between columns remain consistent.

But say you find problems. What are you gonna do about it? Well, Pointblank wants to help at not just finding problems but helping you understand them. When validation failures occur, the detailed reporting capabilities (in the form of beautiful, sharable tables) show you exactly where issues are. Right down to the specific rows and columns. This transforms data validation from a binary pass/fail exercise into a super-insightful diagnostic tool.

Here’s the the best part: Pointblank is designed to work with your existing data stack. Whether you’re using Polars, Pandas, DuckDB, or other database systems, Pointblank tries hard to integrate without forcing you to change your workflow. We also have international spoken language support for reporting, meaning that validation reports can be localized to your team’s preferred language. This making data quality accessible to everyone in your organization (like a team sport!).

Alright! Let’s look at a few demonstrations of Pointblank’s capabilities for data validation.

The Data Validation Workflow

Let’s get right to performing a basic check of a Polars DataFrame. We’ll make use of the included small_table dataset.

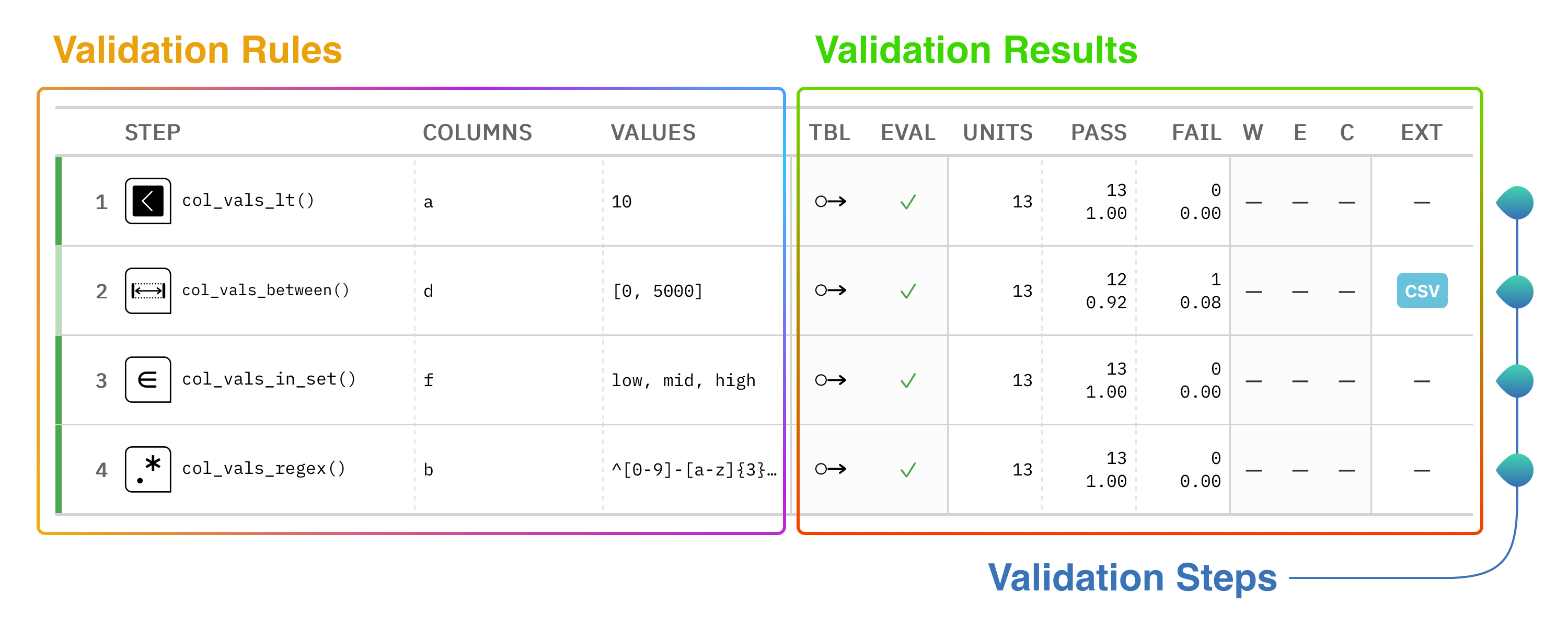

There’s a lot to take in here so let’s break down the code first! Note these three key pieces:

- the

Validate(data=...)argument takes a DataFrame (or database table) that you want to validate - the methods starting with

col_*specify validation steps that run on specific columns - the

interrogate()method executes the validation plan on the table (it’s the finishing step)

This common pattern is used in a validation workflow, where Validate and interrogate() bookend a validation plan generated through calling validation methods.

Now, onto the result: it’s a table! Naturally, we’re using the awesome Great Tables package here in Pointblank to really give you the goods on how the validation went down. Each row in this reporting table represents a single validation step (one for each invocation of a col_vals_*() validation method). Generally speaking, the left side of the validation report tables outlines the key validation rules, and the right side provides the results of each validation step.

We tried to keep it simple in principle, but a lot of useful information can be packed into this validation table. Here’s a diagram that describes a few of the important parts of the validation report table:

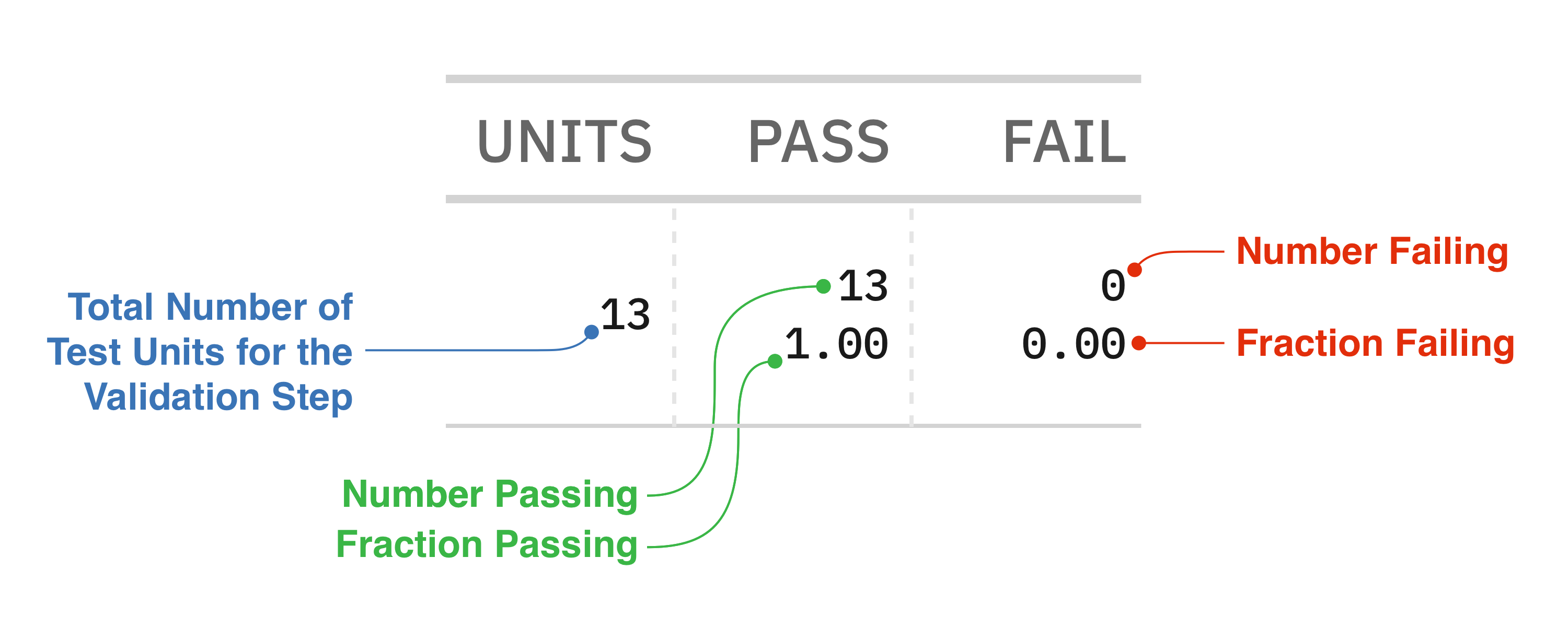

All of those numbers under the UNITS, PASS, and FAIL columns have to do with test units, a measure of central importance in Pointblank. Each validation step will execute a type of validation test on the target table. For example, a col_vals_lt() validation step can test that each value in a column is less than a specified number. The key finding that’s reported as a result of this test is the number of test units that pass or fail. This little diagram explains what those numbers mean:

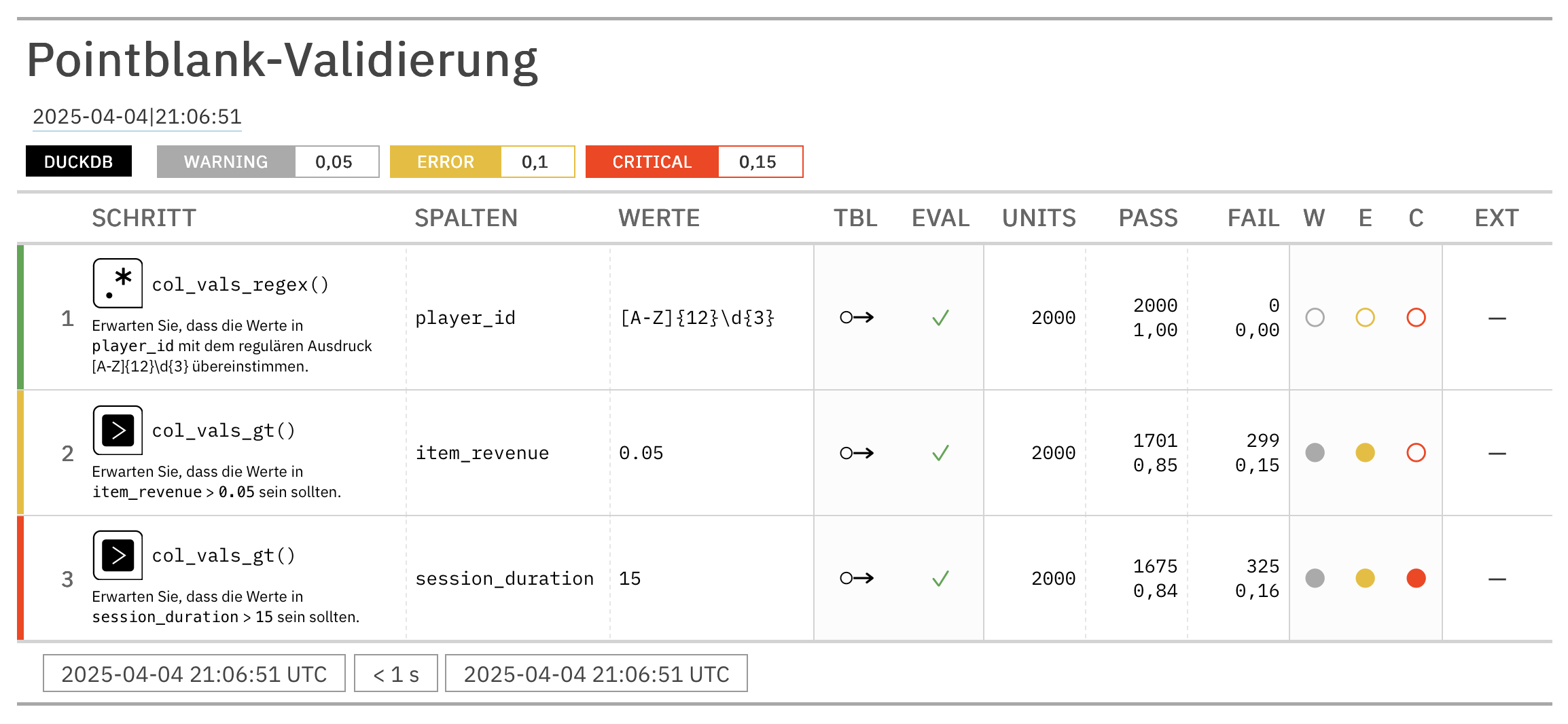

Failing test units can be tied to threshold levels, which can provide a better indication of whether failures should raise some basic awareness or spur you into action. Here’s a validation workflow that sets three failure threshold levels that signal the severity of data quality problems:

import pointblank as pb

import polars as pl

validation_2 = (

pb.Validate(

data=pb.load_dataset(dataset="game_revenue", tbl_type="polars"),

tbl_name="game_revenue",

label="Data validation with threshold levels set.",

thresholds=pb.Thresholds(warning=1, error=20, critical=0.10),

)

.col_vals_regex(columns="player_id", pattern=r"^[A-Z]{12}[0-9]{3}$") # STEP 1

.col_vals_gt(columns="session_duration", value=5) # STEP 2

.col_vals_ge(columns="item_revenue", value=0.02) # STEP 3

.col_vals_in_set(columns="item_type", set=["iap", "ad"]) # STEP 4

.col_vals_in_set( # STEP 5

columns="acquisition",

set=["google", "facebook", "organic", "crosspromo", "other_campaign"]

)

.col_vals_not_in_set(columns="country", set=["Mongolia", "Germany"]) # STEP 6

.col_vals_between( # STEP 7

columns="session_duration",

left=10, right=50,

pre = lambda df: df.select(pl.median("session_duration"))

)

.rows_distinct(columns_subset=["player_id", "session_id", "time"]) # STEP 8

.row_count_match(count=2000) # STEP 9

.col_exists(columns="start_day") # STEP 10

.interrogate()

)

validation_2This data validation makes use of the many validation methods available in the library. Because thresholds have been set at the Validate(thresholds=) parameter, we can now see where certain validation steps have greater amounts of failures. Any validation steps with green indicators passed with flying colors, whereas: (1) gray indicates the ‘warning’ condition was met (at least one test unit failing), (2) yellow is for the ‘error’ condition (20 or more test units failing), and (3) red means ‘critical’ and that’s tripped when 10% of all test units are failing ones.

Reporting tables are essential to the package and they help communicate what went wrong (or well) in a validation workflow. Now let’s look at some additional reporting that Pointblank can give you to better understand where things might’ve gone wrong.

Reporting for Individual Validation Steps

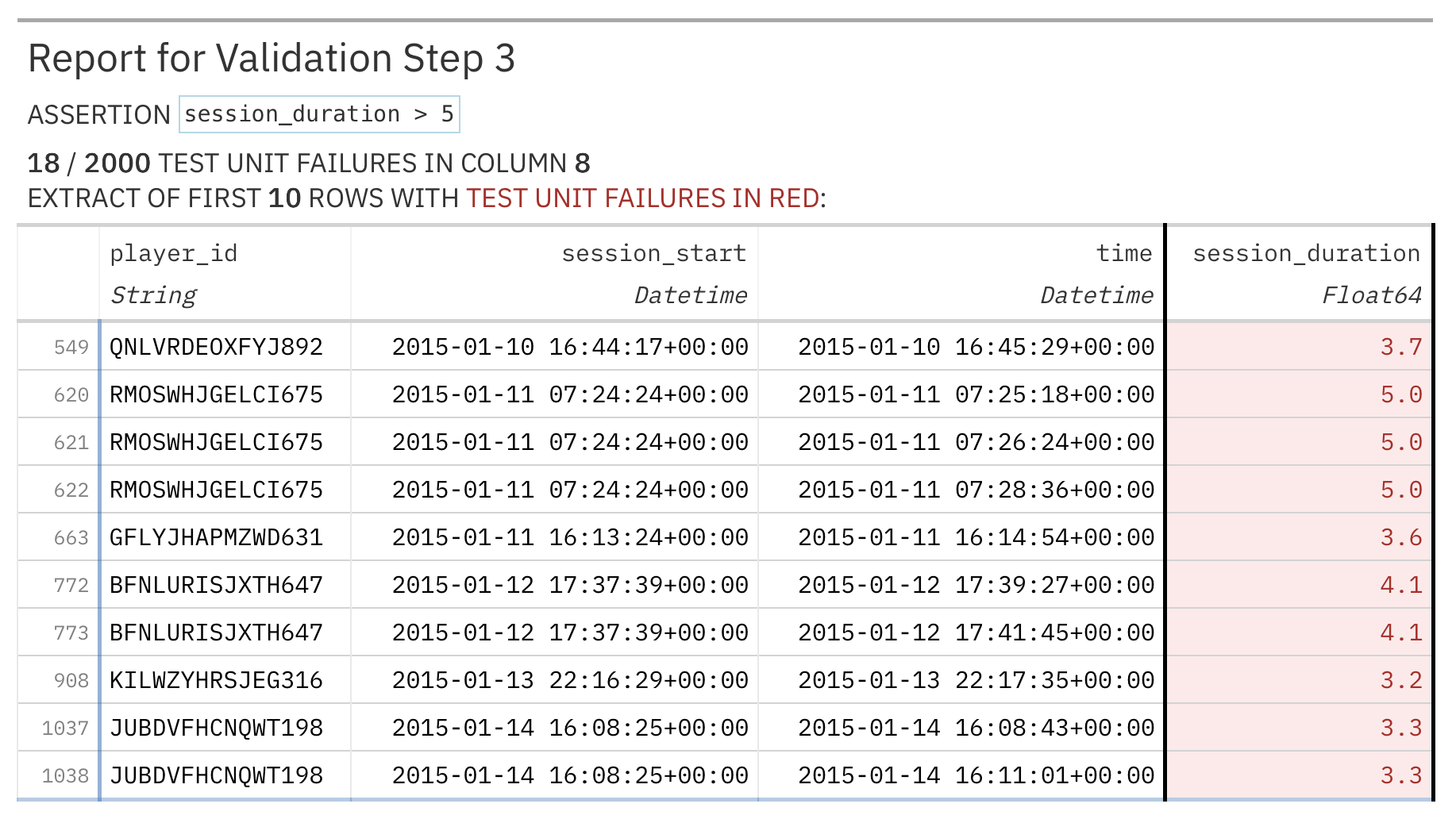

The second validation step of the previous data validation showed 18 failing test units. That translates to 18 spots in a 2,000 row DataFrame where a data quality assertion failed. We often would like to know exactly what that failing data is; it’s usually the next step toward addressing data quality issues.

Pointblank offers a method that gives you a tabular report on a specific step: get_step_report(). The previous tables you’ve seen (the validation report table) dealt with providing a summary of all validation steps. In contrast, a focused report on a single step can help to get to the heart of a data quality issue. Here’s how that looks for Step 2:

validation_2.get_step_report(i=2)| Report for Validation Step 2 ASSERTION 18 / 2000 TEST UNIT FAILURES IN COLUMN 8 EXTRACT OF FIRST 10 ROWS (WITH TEST UNIT FAILURES IN RED): |

|||||||||||

This report provides the 18 rows where the failure occurred. If you scroll the table to the right you’ll see the column that underwent testing (session_duration) is highlighted in red. All of these values are 5.0 or less, which is in violation of the assertion (in the header) that session_duration > 5.

These types of bespoke reports are useful for finding a needle in a haystack. Another good use for a step report is when validating a table schema. Using the col_schema_match() validation method with a table schema prepared with the Schema class allows us to verify our understanding of the table structure. Here is a validation that performs a schema validation with the small_table dataset prepared as a DuckDB table:

import pointblank as pb

# Create a schema for the target table (`small_table` as a DuckDB table)

schema = pb.Schema(

columns=[

("date_time", "timestamp(6)"),

("dates", "date"),

("a", "int64"),

("b",),

("c",),

("d", "float64"),

("e", ["bool", "boolean"]),

("f", "str"),

]

)

# Use the `col_schema_match()` validation method to perform a schema check

validation_3 = (

pb.Validate(

data=pb.load_dataset(dataset="small_table", tbl_type="duckdb"),

tbl_name="small_table",

label="Schema check"

)

.col_schema_match(schema=schema)

.interrogate()

)

validation_3| Pointblank Validation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Schema check DuckDBsmall_table |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| STEP | COLUMNS | VALUES | TBL | EVAL | UNITS | PASS | FAIL | W | E | C | EXT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #4CA64C66 | 1 |

col_schema_match()

|

✓ | 1 | 0 0.00 |

1 1.00 |

— | — | — | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2026-02-26 14:37:22 UTC< 1 s2026-02-26 14:37:23 UTC |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes Step 1 (schema_check) ✗ Schema validation failed: 1 unmatched column(s), 1 dtype mismatch(es). Schema Comparison

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This step fails, but the validation report table doesn’t tell us how (or where). Using `get_step_report() will show us what the underlying issues are:

validation_3.get_step_report(i=1)| Report for Validation Step 1 ✗ COLUMN SCHEMA MATCH COMPLETE IN ORDER COLUMN ≠ column DTYPE ≠ dtype float ≠ float64 |

|||||||

| TARGET | EXPECTED | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLUMN | DATA TYPE | COLUMN | DATA TYPE | ||||

| 1 | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 2 | 2 | ✗ | — | ||||

| 3 | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 4 | 4 | ✓ | |||||

| 5 | 5 | ✓ | |||||

| 6 | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 7 | 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 8 | 8 | ✓ | ✗ | ||||

Supplied Column Schema: [('date_time', 'timestamp(6)'), ('dates', 'date'), ('a', 'int64'), ('b',), ('c',), ('d', 'float64'), ('e', ['bool', 'boolean']), ('f', 'str')] |

|||||||

The step report here shows the target table’s schema on the left side and the expectation of the schema on the right side. There appears to be two problems with our supplied schema:

- the second column is actually

dateinstead ofdates - the dtype of the

fcolumn is"string"and not"str"

The convenience of this step report means we only have to look at one display of information, rather than having to collect up the individual pieces and make careful comparisons.

Much More in Store

Pointblank tries really hard to make it easy for you to test your data. All sorts of input tables are supported since we integrate with the brilliant Narwhals and Ibis libraries. And even through the project has only started four months ago, we already have an extensive catalog of well-tested validation methods.

We care a great deal about documentation so much recent effort has been placed on getting the User Guide written. We hope it provides for gentle introduction to the major features of the library. If you want some quick examples to get your imagination going, check out our gallery of examples.

We really care about what you want in a validation package, so talk to us :) We just started a Discord so feel free to hop on and ask us anything. Alternatively, we always like to get issues so don’t be shy in letting us know how we could improve!